The Post-GMO Economy

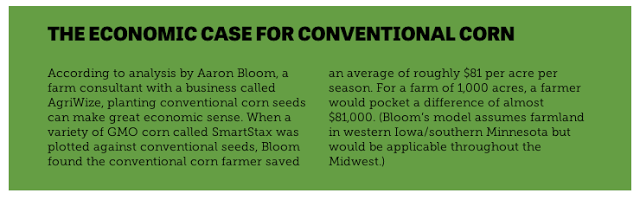

One mainstream farmer is returning to conventional seed — and he’s not alone

As an invulnerable tween, Chris Huegerich, the child of a prosperous farming family, wiped out on his motorcycle in tiny Breda, Iowa. Forty years on, folks still call Huegerich “Crash.” And though he eventually went down a conventional path (married, divorced) and bought out his parents’ farm, Huegerich has recently reverted to his daredevil ways — at least when it comes to choosing what kind of corn to plant.

It’s late November, and Huegerich’s 2,800 acres in central Iowa have been neatly shorn to sepia-and-umber stubble. His enormous combines and cultivators have been precision parked — wheel nut to headlight — inside his equipment sheds. But in Huegerich’s office, between the fields and the sheds, chaos reigns. A dozen dog-eared seed catalogs litter a table, along with marked-up spreadsheets and soil maps. For farmers choosing next year’s crop, this is decision time.

|

| Huegerich, in his combine. He has no ideological problem with GMOs but has been experimenting with conventional seeds for financial reasons |

Buying seeds used to be a fairly simple matter. Farmers picked four or five varieties offered by a regional dealer, and that was that. But in the mid-1990s, biotech companies started producing seeds genetically modified with traits from other organisms. One trait made soybeans resistant to the herbicide glyphosate; another, using a protein from the soil bacterium Bt, helped corn fend off the insects rootworm and European corn borer.

Huegerich’s father eagerly embraced the new genetically modified (GMO) seeds. They cost more, but he could save money on herbicides and pesticides. His yields and profits went up, helped in part by good weather and favorable market conditions. But as revenue rose and the years passed, trouble was looming.

“Five years ago the traits worked,” says the strongly built Huegerich, who followed in his father’s footsteps and planted GMO seeds. “I didn’t have corn rootworm because of the Bt gene, and I used less pesticide. Now, the worms are adjusting, and the weeds are resistant. Mother Nature adapts.”

Staring at a future of lower corn prices and higher inputs, Huegerich decided to experiment. Two years ago, he planted 320 acres of conventional corn and 1,700 with GMO corn. To his delight, the conventional fields yielded 15 to 30 more bushels per acre than the GMO fields, with a profit margin of up to $100 more per acre. And so in 2013, he upped the ante, ordering six varieties of conventional seeds for close to 750 acres and GMOs for his remaining acres.

|

| Attachments for a skid loader sit stacked near the silos at Huegerich’s home base. After harvest, Huegerich has a busy winter planning for next year’s crop. |

Hugerich Isn’t the only farmer retreating from GMO seeds. In pockets across the nation, commodity growers are becoming fed up with traits that don’t work like they used to. Not only are the seeds expensive (GMO corn can cost $150 more per bag than conventional corn), they’re also driving farmers to buy and apply more chemicals. During the growing season, Huegerich sprays both his conventional and his GMO corn twice with herbicides and twice with pesticides, despite the GMO’s theoretical resistance to rootworm. “It gives me peace of mind,” Huegerich says. Between 2001 and 2010, the consumer advocacy group Food & Water Watch reports, total on-farm herbicide use increased 26 percent as weed resistance grew. Today, 61.2 million acres of cropland, including many of Huegerich’s, are plagued by glyphosate-resistant weeds.

Just as plants and animals adapt to environmental pressures, retailers respond to consumer pressure. This past March, Whole Foods announced that by 2018 it would label all its foods containing genetically engineered ingredients. In June, Target announced it would debut a line of foods, called Simply Balanced, that would be free of genetically modified ingredients by the end of 2014. And by late summer, more than 20 states were considering genetic modification label laws.

While consumer demand will ultimately propel more non-GMO grain into the market, more proximate factors can also influence what kinds of seeds farmers plant. For example, geography. Does the grower live close to the river systems that send the vast majority of the nation’s conventional grain to GMO-averse markets in Japan, South Korea and the EU? Wyatt Muse, a merchandiser for Clarkson Grain, which buys conventional and organic corn and soybeans, pays farmers a premium — up to $2 extra per bushel over the base commodity price of soybeans, $1 for corn — to not only grow the crop but also preserve its identity. (That is, keep it separate from genetically modified grain all the way from planting through harvest, storage and transportation.)

Huegerich doesn’t live near a dry mill that would pay him a premium for conventional corn, or a river that can move his product out into the world. But he does live within trucking distance of Blair, Nebraska, where a Cargill-owned plant converts his crop into plastic for customers who want a bio-based product but can’t get behind GMO corn. “I get a fifty-cent-per-bushel premium,” Huegerich says.

Aaron Bloom doesn’t farm near an outlet that pays a premium, but he still comes out ahead with conventional corn. A crop consultant, Bloom has been experimenting with non-GMO varieties for five years on land he works around Cherokee, Iowa. “We get the same or better yields, and we save money up front,” he says. And yet when he first suggests conventional seeds to clients, he sometimes gets pushback. “Guys think that you have to get out the cultivator” — which pierces the soil between rows of crops — “and kill your weeds by hand. No! You’re going out there with the planter anyway, just add your insecticide and your conventional herbicides.” Last year, not one of the roughly 30 farmers to whom Bloom sold non-GMO seeds had a bad harvest — despite unprecedented drought. “And I’ve got another 20 trying this year.”

Still, winning converts to conventional corn can be an uphill slog. Post-harvest, farmers face a barrage of TV and print ads touting the latest seed technology. There’s a subtler psychology at work, too. Farmers have close relationships with their seed dealers, who often live nearby and keep them company at local baseball games, PTA meetings or church. “You can’t break up with them,” Bloom says, noting that seed dealers work on commission. DuPont Pioneer, for example, offers him a non-GMO corn for $180 a bag, while Wyffels Hybrids sold the same for $115 a bag last year.

Why does Pioneer charge so much? Because it doesn’t want lower-priced conventional seed to lure customers away from GMOs. Bloom says a company dealer confessed: “We don’t want our farmers to buy it.”

|

| From left: Rotary hoes neatly stacked in Huegerich’s shop; The corn combine shows some attitude. |

Into this breach, smaller companies that specialize in non-GMO seed have leapt. West Des Moines–based eMerge Genetics has averaged 30 percent growth in each of the last five years. Sales at Spectrum Seed Solutions, based in Linden, Indiana, have doubled every year of the four it’s been in business. Its president, Scott Odle, believes that non-GMO corn could be 20 percent of the market in five years. After surveying 10 smaller companies focusing on conventional seed in the grain belt earlier this year, Ken Roseboro, editor of The Organic & Non-GMO Report, reported that each saw an increase in demand. “And I think it’s going to continue,” he says.

But are there more acres of conventional corn being planted, or are small seed companies simply filling a niche that larger companies have relinquished? It’s difficult to say. Jeffrey Neu, a Monsanto spokesperson, says, “While we offer some conventional hybrids, we continue to see the greatest demand for ‘traited’ products. We typically do not provide percentage or sales information.” Daniel Jones, a business manager at DuPont Pioneer, says sales of his company’s conventional seeds have “trended up,” but he declines to say by how much. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 88 percent of the corn planted in the nation in 2011 and 2012 was genetically modified; in 2013, the percentage rose to 90. Because the total acreage of corn is so huge — 97 million acres — it obscures the acreage planted by farmers like Huegerich and Bloom. “The growth is regional and local,” Wyatt Muse of Clarkson Grain says, “so it won’t show up in the national data.”

|

| Aaron Bloom, a farmer and business consultant at Huegerich’s farm; |

The big seed companies are carefully watching state legislatures, spending tens of millions of dollars to defeat proposed labeling laws and fielding calls from food companies concerned with how such laws could impact production agriculture. “If such laws create a demand at the farmer level, we’ll have to respond,” Pioneer’s Jones says, cautiously. “But we won’t lead the charge.” Chuck Hill, specialty products manager at AgriGold Hybrids, which sells both GMOs and hybrids, sounds a similarly wary note: “Whole Foods’ decision to label was not an earthshaker,” he insists. “The company was already serving that clientele. Now, if Walmart decided to label GM food, that would be a major chit.”

And yet this parallel seed economy is churning. The Non-GMO Project, which offers third-party verification and labeling for non-GMO products, has been inundated with requests from food purveyors for information about enrolling their products, and consumer spending on non-GMO-verified products rose from $1.3 billion to $3.1 billion between 2011 and 2013. Companies that make non-GMO feed for animals, says Caroline Kinsman, communications manager for the Non-GMO Project, are experiencing “incredible demand.”

|

| From left: A sign in the town of Breda, Iowa; Non-GMO corn shows its stuff at one of Huegerich’s farms |

Sales at Hiland Naturals, which makes conventional and organic feeds for livestock, have more than doubled since it received Non-GMO Project verification last year. Most of Hiland’s customers are small farmers who sell eggs or meat at farmers markets and natural grocery stores. But many sell birds to Whole Foods and to institutions like colleges. Some of Hiland’s growth, owner Dan Masters says, comes from people wanting to know what they’re eating, some is from pending labeling laws and some is from “people who are tired of big corporations and big agriculture.”

As farmers across the grain belt were contemplating what they’d plant next spring, Masters was in talks with one of the nation’s largest animal feed producers to formulate a non-GMO-verified product. Should the deal come to fruition, it would more than double his company’s size and trigger the opening of several more mills.

“We need to get more farmers on board with conventional seed now,” Aaron Bloom says, anticipating the market’s growth. “We need to be innovative and grow toward the demand of the consumer.”

The article was produced in collaboration with the Food & Environment Reporting Network, an independent, non-profit news organization producing investigative reporting on food, agriculture and environmental health.